The first-ever economic study on the downstream EU aluminium industry conducted by LUISS University in Rome unveils the magnitude of the damage inflicted on EU SME’s and the unfair competitive advantages given to EU and extra-EU producers by the current import tariff regime and the financial diversions it permits.

The maintaining by the European Union of an economically unjustified import duty on primary aluminium has imposed up to 15.5 billions Euros additional costs to downstream aluminium SMEs in the past fourteen years, seriously impinging on their competitiveness, and has allowed producers of this metal in and outside Europe to cash-in important artificial benefits to the detriment of the competitiveness of the EU aluminium industry. This extra-cost is due to the fact that all producers of primary aluminium artificially include an equivalent of the value of the 6% import duty on all the metal sold into the EU, irrespective of its origin.

Summary of key facts and findings

The LUISS Study is the first ever comprehensive analysis of the EU aluminium industry that focuses on the downstream sector, which represents around 90% of the EU aluminium industry’s workforce. Conducted with the support of the Federation of Aluminium Consumers in Europe (FACE), one of its key findings is the estimate of the cumulated cost incurred by EU downstream firms imposed by the EU import tariffs on primary aluminium over the period 2000-2013.

According to four different scenarios considered, the cumulated cost of the import tariff borne by downstream firms is estimated to be between €5.5 billion and €15.5 billion.

Only a marginal share of such an amount is actually collected by EU Customs. The remainder constitutes extra revenues for EU and extra-EU firms, typically big and vertically integrated. Primary aluminium tariffs artificially inflate the costs of semi-finished and finished aluminium products and, combined with the increasing competitive pressure stemming from extra-EU producers, progressively endangers downstream firms based in the EU, thus weakening the international competitiveness of the entire EU aluminium value chain. The study strongly recommends the suppression of the duty on primary aluminium imports, for several reasons:

- EU is already largely dependent on primary aluminium imports and domestic production capacity can cover only 45% of the EU apparent consumption of primary aluminium;

- EU trade policy is harming the competitiveness of the heart of the EU aluminium industry, as downstream activities (extruding, rolling and casting) currently employ more than 90% of the total workforce in the EU aluminium industry;

- the effects of the duty contradict the spirit of the Lisbon Treaty. EU trade policy is limiting economic initiatives in downstream aluminium activities, penalising SMEs and explicitly favouring big vertically integrated producers.

Summary

The first study on the competitiveness of the EU downstream aluminium industry

The CRIF “Fabio Gobbo” of the LUISS “Guido Carli” University of Rome has conducted a unique research in order to analyse the impacts of EU policies on the downstream sector of the EU aluminium industry, i.e. firms producing semi-finished aluminium products, with the support of the Federation of Aluminium Consumers in Europe (FACE). The ultimate goal of the study is to stress the critical issues currently affecting the sector, with particular reference to EU trade policy and primary aluminium duties, and provide policy recommendations that foster the global competitive position of EU downstream firms. While the overall results of the study will be presented in December, some of its main findings are briefly disclosed because of their relevance.

The LUISS Study is the first ever comprehensive analysis of the EU aluminium industry that focuses on the downstream sector, which represents around 90% of the EU aluminium industry’s workforce.

Previous studies have mainly considered the upstream segment of the industry, i.e. producers of primary aluminium. In particular, the DG Enterprise & Industry of the European Commission has first promoted a study focusing on EU non-ferrous metal producers1 and later launched a new round of studies aiming at analysing the impacts of EU policies and rules on the international competitiveness of the steel and aluminium industries2. However, these analyses are essentially limited to primary aluminium producers, which represent only a part of the aluminium industry as they employ about 10% of the entire sector’s labour force. This clearly neglects the fundamental role played by downstream segments that use aluminium to produce a wide range of products that in turn are growingly employed in many industries (automotive, buildings, etc.). The only relatively significant reference to the downstream sector is the Ecorys report that estimates that a 1% reduction in the EU import tariff on primary aluminium would reduce production costs for downstream firms by €117 millions.

The LUISS Study fills this gap by providing an in-depth analysis of the whole downstream sector. After having performed a sectorial analysis of the EU aluminium industry with a special focus on producers of semi-finished products, the study examines in depth the most relevant factors for the competitiveness of EU downstream firms. It focuses on the functioning of the global aluminium market, the price formation process and the impact of the EU trade policy on downstream activities. One of the key findings of the study is the estimate of the cumulated cost incurred by EU downstream firms over the period 2000-2013 imposed by the EU import tariffs on primary aluminium.

The cumulated cost of the import tariffs borne by downstream firms is estimated to be between €5.5 billion and €15.5 billion (in 2013 real Euros).

This large variability in the estimate stems from four different scenarios that the LUISS team of researchers has considered. In particular, the study explores different assumptions about either the quantity of aluminium affected by the EU import tariffs and the magnitude of the resulting impact on aluminium market prices. Importantly, all of the estimates rest upon the fact that the import tariff affects not only the price of dutiable primary aluminium but also the price of non-dutiable aluminium sold in the EU.

This fact artificially inflates the costs of semi-finished and finished aluminium products and, combined with the increasing competitive pressure stemming from extra-EU producers, progressively endangers downstream firms based in the EU, thus weakening the international competitiveness of the entire EU aluminium production chain.

The four estimates on the cumulated costs of the import duty are summarised here below.

In the first scenario (lower bound), the extra-cost for the downstream industry generated by the duty is €5.5 billion. While only €885 million (16% of these extra-costs) result in additional EU Customs revenues, €2.2 billion (40%) accrue as extra-revenues to EU smelters and €2.5 billion (44%) accrue as extra-revenues to extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU.

In the second scenario (lower bound “plus”), the total extra-costs are estimated to be €8.7 billion. 11% of these extra-costs (€1 billion) result in additional Customs revenues for the EU. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra revenues of €2.2 billion (25%) for EU smelters, €3.0 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €2.5 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU market.

In the third scenario (upper bound), the duty causes a cumulated extra-cost of €9.6 billion. This cost generates €1.5 billion of additional EU Customs revenues (16% of the total cost), more than €3.8 billion (40%) of extra-revenues for EU smelters, and €4.3 billion (45%) of extra-revenues for extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU market.

Finally, in the fourth scenario (upper bound “plus”), the extra-costs are equal to €15.5 billion. Only €1.7 billion of these extra-costs (11%) accrue to the EU as Customs revenues. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra-revenues of €4.0 billion (25%) for EU producers of primary aluminium, €5.3 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €4.6 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU Customs Union.

In light of the above, the study recommends the suppression of the duty on primary aluminium imports on different grounds.

First, if the rationale for the existence of a duty is to sustain primary aluminium production and/or to substitute imports, this tool is missing the mark. Currently, the EU nearly has a fully exploited production capacity and extensively draws upon imports of unwrought aluminium to satisfy its needs. Furthermore, the EU aluminium primary production shrank in the last decade and new investments aiming at increasing capacity to meet a growing demand were made only in extra-EU countries. Second, not only the EU trade and industrial policies on aluminium tariffs are missing the mark but they are harming the competitiveness of the heart of the EU aluminium industry as downstream activities (extruding, rolling and casting) currently employ more than 90% of the total workforce in the EU aluminium industry. Third, the costs imposed by EU trade policy on downstream activities could be even larger in the near future. As a matter of fact, the cumulated cost of the import duty estimated in the study includes the period

2008-2013, when the fall of global demand substantially lowered prices. The combined effect of an increase in aluminium prices due to global recovery (the demand for aluminium products is expected to experience a 6% annual growth in next years) and an expected rise of EU aluminium premiums deriving from the structural EU shortage would magnify the negative impact of the import duty on downstream firms. Last but not least, the effects of the duty contradict the spirit of the Lisbon Treaty.

The current EU trade and industrial policy on aluminium tariffs is limiting economic initiatives in downstream aluminium activities, penalising SMEs and explicitly favouring big vertically integrated producers, notably outside Europe.

CONTACTS:

LUISS UNIVERSITY

Davide Quaglione

CRIF “Fabio Gobbo”, via Tommaso Salvini n. 2, 00197 Roma

Tel. +39-6-85225720

Email: dquaglione@luiss.it

FACE

Mario Conserva

Federation of Aluminium Consumers in Europe

Rond Point Schuman 6, Box 5

B-1040 Brussels

Belgium

Ph. Mob .+335 7194359

Email: Mario.conserva@edimet.com

Missing the mark and killing the heart: how EU aluminium trade policy is imposing billions of Euros on EU SMEs and final consumers / Some duties are bigger than others. European aluminium trade policy costs several billions Euros to downstream aluminium SMEs.

by Ernesto Cassetta, Michele Crescenzi, Linda Meleo, Cesare Pozzi, Davide Quaglione, Felice Simonelli, CRIF/LUISS “Guido Carli”

The CRIF “Fabio Gobbo” of the LUISS “Guido Carli” University of Rome has conducted a unique research in order to analyse the impacts of EU policies on the downstream sector of the EU aluminium industry, i.e. firms producing semi-finished aluminium products, with the support of the Federation of Aluminium Consumers in Europe (FACE). The ultimate goal of the study is to stress the critical issues currently affecting the sector, with particular reference to EU trade policy and primary aluminium duties, and provide policy recommendations that foster the global competitive position of EU downstream firms.

The LUISS Study is the first ever comprehensive analysis of the EU aluminium industry that focuses on the downstream sector. Previous studies have mainly considered the upstream segment of the industry, i.e. producers of primary aluminium. In particular, the DG Enterprise & Industry of the European Commission has first promoted a study focusing on EU non-ferrous metal producers1 and later launched a new round of studies aiming at analysing the impacts of EU policies and rules on the international competitiveness of the steel and aluminium industries2.

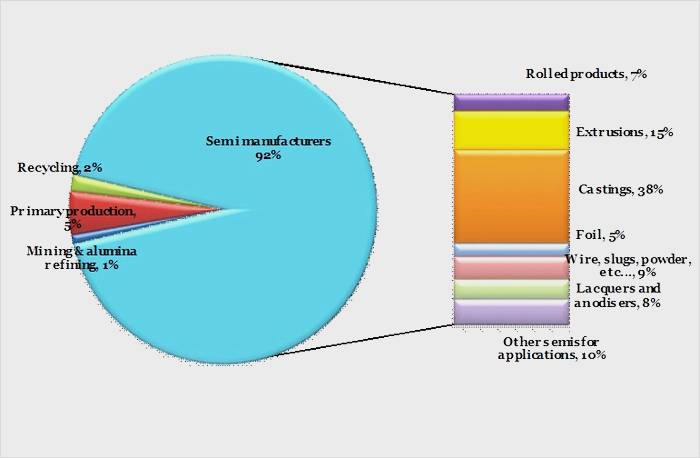

However, these analyses are essentially limited to primary aluminium producers, which represent only a part of the aluminium industry as they employ about 8% of the entire sector’s labour force (see Figure 1). This clearly neglects the fundamental role played by downstream segments that use aluminium to produce a wide range of products that in turn are growingly employed in many industries (automotive, buildings, etc.). The only relatively significant reference to the downstream sector is the Ecorys report that estimates that a 1% reduction in the EU import tariff on primary aluminium would reduce production costs for downstream firms by €117 million.

1) Cf. Competitiveness of the EU Non-ferrous Metals Industries, Ecorys, 2011.

2) Cf. Assessment of Cumulative Cost Impact for The Steel and The Aluminium Industry, Final Report Aluminium, CEPS & Economisti Associati, 2013.

FIGURE 1. TOTAL EMPLOYMENT IN THE EU ALUMINIUM INDUSTRY BY SECTOR/SEGMENT, 2011

The LUISS Study fills this gap by providing an in-depth analysis of the whole downstream sector. After having performed a sectorial analysis of the EU aluminium industry with a special focus on producers of semi-finished products, the study examines in depth the most relevant factors for the competitiveness of EU downstream firms. It focuses on the functioning of the global aluminium market, the price formation process and the impact of the EU trade policy on downstream activities.

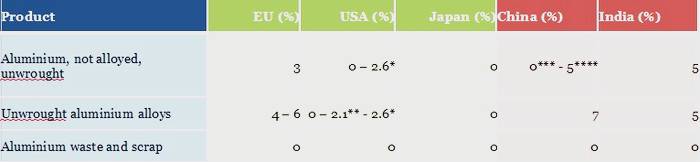

One of the key findings of the study is the estimate of the cumulated cost incurred by EU downstream firms over the period 2000-2013 imposed by the EU import tariff on primary aluminium. An overview of the current tariff regimes worldwide is provided in Table 1, which shows the current level of Most Favoured Nation (MFN) import tariffs for aluminium products in selected countries in 2014.

TABLE 1. MFN IMPORT TARIFFS FOR ALUMINIUM PRODUCTS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES, 2014

Notes: *76011030 & 76012030 of uniform cross section throughout its length, the least cross-sectional dimension of which is not greater than 9.5 mm, in coils; ** 76012060 containing 25 percent or more by weight of silicon; *** 7601010 other unwrought unalloyed aluminium; **** 76011010 unwrought aluminium containing 99.95% or more of aluminium.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration on WTO Tariff Download Facility, Unites States International Trade Commission Database, and Japan’s Tariff Schedule.

The cumulated cost of the import tariff borne by downstream firms is estimated to be between €5.5 billion and €15.5 billion (in 2013 real Euros). This large variability in the estimate stems from four different scenarios that the LUISS team of researchers has considered. In particular, the study explores different assumptions about either the quantity of aluminium affected by the EU import tariffs and the magnitude of the resulting impact on aluminium market prices. Importantly, all of the estimates rest upon the fact that the import tariff affects not only the price of dutiable primary aluminium but also the price of non-dutiable aluminium sold in the EU. This fact artificially inflates the costs of semi-finished and finished aluminium products and, combined with the increasing competitive pressure stemming from extra-EU producers, progressively endangers downstream firms based in the EU, thus weakening the international competitiveness of the entire EU aluminium production chain. The four estimates on the cumulated costs of the import duty are summarized here below and reported in Table 2.

In the first scenario (lower bound), the extra-cost for the downstream industry generated by the duty is €5.5 billion. While only €885 million (16% of these extra-costs) result in additional EU Customs revenues, €2.2 billion (40%) accrue as extra-revenues to EU smelters and €2.5 billion (44%) accrue as extra-revenues to extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU.

In the second scenario (lower bound “plus”), the total extra-costs are estimated to be €8.7 billion. 11% of these extra-costs (€1 billion) result in additional Customs revenues for the EU. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra revenues of €2.2 billion (25%) for EU smelters, €3.0 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €2.5 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU market.

In the third scenario (upper bound), the duty causes a cumulated extra-cost of €9.6 billion. This cost generates €1.5 billion of additional EU Customs revenues (16% of the total cost), more than €3.8 billion (40%) of extra-revenues for EU smelters, and €4.3 billion (45%) of extra-revenues for extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU market.

Finally, in the fourth scenario (upper bound “plus”), the extra-costs are equal to €15.5 billion. Only €1.7 billion of these extra-costs (11%) accrue to the EU as Customs revenues. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra-revenues of €4.0 billion (25%) for EU producers of primary aluminium, €5.3 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €4.6 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU Customs Union.

TABLE 2. CUMULATED COST OF THE EU IMPORT DUTY ON PRIMARY ALUMINIUM, 2000-2013,

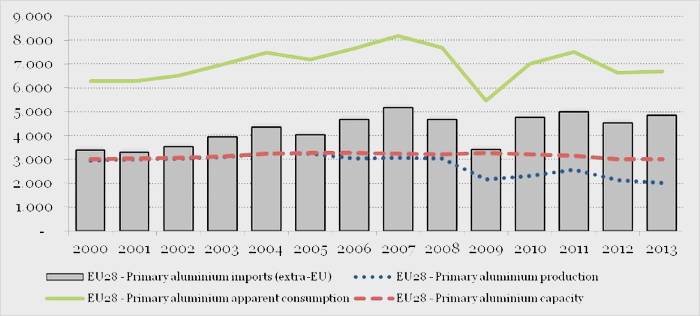

In light of the results above, the study recommends the suppression of the duty on primary aluminium imports on different grounds. First, if the rationale for the existence of a duty is to sustain primary aluminium production and/or to substitute imports, this tool is missing the mark. As shown in Figure 2, the EU nearly has a fully exploited production capacity and extensively draws upon imports of unwrought aluminium to satisfy its needs. Furthermore, the EU aluminium primary production shrank in the last decade and new investments aiming at increasing capacity to meet a growing demand were made only in extra-EU countries. Second, not only the EU trade policy is missing the mark but it is harming the competitiveness of the heart of the EU aluminium industry as downstream activities (extruding, rolling and casting) currently employ more than 90% of the total workforce in the EU aluminium industry. Third, the costs imposed by EU trade policy on downstream activities could be even larger in the near future. As a matter of fact, the cumulated cost of the import duty estimated in the study includes the period 2008-2013, when the fall of global demand substantially lowered prices. The combined effect of an increase in aluminium prices due to global recovery (the demand for aluminium products is expected to experience a 6% annual growth in next years) and an expected rise of EU aluminium premiums deriving from the structural EU shortage would magnify the negative impact of the import duty on downstream firms. Last but not least, the effects of the duty contradict the spirit of the Lisbon Treaty. EU trade policy is limiting economic initiatives in downstream aluminium activities, penalizing SMEs and explicitly favouring big vertically integrated producers, notably outside Europe.

FIGURE 2. EU-28 APPARENT CONSUMPTION, IMPORTS, PRODUCTION AND INSTALLED CAPACITY OF PRIMARY ALUMINIUM, 2000-2013, THOUSANDS OF TONNES

The cumulated cost of the import tariff borne by downstream firms is estimated to be between €5.5 billion and €15.5 billion (in 2013 real Euros). This large variability in the estimate stems from four different scenarios that the LUISS team of researchers has considered. In particular, the study explores different assumptions about either the quantity of aluminium affected by the EU import tariffs and the magnitude of the resulting impact on aluminium market prices. Importantly, all of the estimates rest upon the fact that the import tariff affects not only the price of dutiable primary aluminium but also the price of non-dutiable aluminium sold in the EU. This fact artificially inflates the costs of semi-finished and finished aluminium products and, combined with the increasing competitive pressure stemming from extra-EU producers, progressively endangers downstream firms based in the EU, thus weakening the international competitiveness of the entire EU aluminium production chain. The four estimates on the cumulated costs of the import duty are summarized here below and reported in Table 2.

In the first scenario (lower bound), the extra-cost for the downstream industry generated by the duty is €5.5 billion. While only €885 million (16% of these extra-costs) result in additional EU Customs revenues, €2.2 billion (40%) accrue as extra-revenues to EU smelters and €2.5 billion (44%) accrue as extra-revenues to extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU.

In the second scenario (lower bound “plus”), the total extra-costs are estimated to be €8.7 billion. 11% of these extra-costs (€1 billion) result in additional Customs revenues for the EU. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra revenues of €2.2 billion (25%) for EU smelters, €3.0 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €2.5 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU market.

In the third scenario (upper bound), the duty causes a cumulated extra-cost of €9.6 billion. This cost generates €1.5 billion of additional EU Customs revenues (16% of the total cost), more than €3.8 billion (40%) of extra-revenues for EU smelters, and €4.3 billion (45%) of extra-revenues for extra-EU smelters that have duty free access to the EU market.

Finally, in the fourth scenario (upper bound “plus”), the extra-costs are equal to €15.5 billion. Only €1.7 billion of these extra-costs (11%) accrue to the EU as Customs revenues. The artificial price increase caused by the EU import tariffs leads to extra-revenues of €4.0 billion (25%) for EU producers of primary aluminium, €5.3 billion (34%) for EU remelters and refiners, and €4.6 billion (30%) for extra-EU primary and secondary producers that have duty free access to the EU Customs Union.

TABLE 2. CUMULATED COST OF THE EU IMPORT DUTY ON PRIMARY ALUMINIUM, 2000-2013,

In light of the results above, the study recommends the suppression of the duty on primary aluminium imports on different grounds. First, if the rationale for the existence of a duty is to sustain primary aluminium production and/or to substitute imports, this tool is missing the mark. As shown in Figure 2, the EU nearly has a fully exploited production capacity and extensively draws upon imports of unwrought aluminium to satisfy its needs. Furthermore, the EU aluminium primary production shrank in the last decade and new investments aiming at increasing capacity to meet a growing demand were made only in extra-EU countries. Second, not only the EU trade policy is missing the mark but it is harming the competitiveness of the heart of the EU aluminium industry as downstream activities (extruding, rolling and casting) currently employ more than 90% of the total workforce in the EU aluminium industry. Third, the costs imposed by EU trade policy on downstream activities could be even larger in the near future. As a matter of fact, the cumulated cost of the import duty estimated in the study includes the period 2008-2013, when the fall of global demand substantially lowered prices. The combined effect of an increase in aluminium prices due to global recovery (the demand for aluminium products is expected to experience a 6% annual growth in next years) and an expected rise of EU aluminium premiums deriving from the structural EU shortage would magnify the negative impact of the import duty on downstream firms. Last but not least, the effects of the duty contradict the spirit of the Lisbon Treaty. EU trade policy is limiting economic initiatives in downstream aluminium activities, penalizing SMEs and explicitly favouring big vertically integrated producers, notably outside Europe.

FIGURE 2. EU-28 APPARENT CONSUMPTION, IMPORTS, PRODUCTION AND INSTALLED CAPACITY OF PRIMARY ALUMINIUM, 2000-2013, THOUSANDS OF TONNES